The Federal Constitution grants to Sabah and Sarawak a number of iron-clad guarantees of their autonomy and special position.

THE “Borneoisation case” of Fung Fon Chen @ Bernard v Govt (2012) is slated for rehearing on July 23. It relates to alleged violations of Sabah and Sarawak’s special position in the Federal set-up.

When Sabah, Sarawak and Singapore joined hands with Malaya to constitute Malaysia, the significantly amended Federal Constitution granted them a number of iron-clad guarantees of their autonomy and special position.

Some in the peninsula feel that 52 years after Malaysia Day the special rights and privileges must give way to more unity and uniformity on such issues as right to travel, live and work throughout the Federation. Many Sabahans and Sarawakians, on the other hand, lament that they have been shortchanged and that there is a distinct whittling down of the privileges promised to them in 1963.

Gleaning over existing literature, a list of the main complaints may run as follows:

Political control: The Federal Government dictates political outcomes. The Federal Government’s choice of Mentris Besar and Governors does not always reflect popular sentiments in these states. The declaration of emergency in Sarawak in 1966 and the dismissal of Chief Minister Stephen Kalong Ningkan indicate that state autonomy is rather frail. Interference by Federal politicians in Sabah’s politics in 1994 led to the replacement of popularly elected local leaders.

Expanding Federal jurisdiction: Labuan was ceded to the Federal Government in 1984. Water and tourism have been federalised. Federal trespass on Sabah and Sarawak’s right in relation to amendments to the Federal Constitution was highlighted in the landmark decision of Robert Linggi vs Government of Malaysia (2011).

Religion: At the time of the 1963 merger, there was no state religion in these two states. Islam is now the official religion of Sabah. Articles 161C and 161D, which imposed procedural restrictions on laws favouring Islam, were repealed in 1976. The seizure of Bibles and the judicial decision on the kalimah Allah issue have angered many Sabahans and Sarawakians.

Finances: There is an allegation that these states do not derive the kind of financial benefit they deserve as a result of their contribution to the national coffers from petroleum, hydroelectricity and tourism.

Immigration: The influx of illegal immigrants and the alleged ‘’naturalisation’’ of thousands of them are violations of Sabah and Sarawak’s right over immigration.

Parliamentary representation: In 1963 it was envisaged that the Borneo states and Singapore shall have no less than 33% of the Dewan Rakyat seats. The percentage has now dipped to 25%.

20-Point Agreement: Within Sabah there is considerable disquiet that some of the safeguards of the ‘’20 Points’’ have not been converted to law. A prominent complaint is that Borneoisation of public services in Sabah has not proceeded vigorously. It is alleged that insufficient protection is being given under Article 153 to natives of Borneo states.

Secession: In the light of the above, a movement has sprung up asking for Sabah to secede from the Federation. Legally speaking, our Constitution contains no provision for the secession of any state from the Federation. The disintegration of the Federal union is not contemplated by the Constitution. Any attempt at separation or incitement to secede will actually amount to treason and sedition under our criminal laws.

Even the 20-Point Agreement with Sabah explicitly states in para 7 that there is no right to secession.

But what about Singapore? Contrary to what is believed by some, Singapore did not unilaterally secede from Malaysia. Its “separation” was accomplished by several mutual acts between the Malaysian Federal Government and the state Government of Singapore.

Among these were the Independence of Singapore Agreement 1965 and the Constitution and Malaysia (Singapore Amendment) Act 1965. The latter made significant modifications to the 1957 Federal Constitution and the 1965 Malaysia Act and explicitly stated, “Parliament may by this Act allow Singapore to leave Malaysia”.

Self-determination: What about international law? One has to concede that the law of nations recognises the right of a people to self-determination. The law was born in an era of decolonisation and embraces the notion that people who have a common historical, ethnic, cultural, linguistic, religious, ideological, territorial or economic identity have a right to determine the political and legal status of their territory. They may set up a new State or choose to become part of another State.

In recent memory, Crimea (2014), Timor Leste (1995) and Bangladesh (1971) travelled down the painful, blood-soaked path of national liberation.

The principle of self-determination is recognised in Articles 1(2), 55, 73 and 76(b) of the United Nations Charter and in many other international documents. However, international law scholar Abdul Ghafur Hamid asserts that the legal right of self-determination applies primarily to colonised, trust and mandated territories: “The effect of linking self-determination to decolonisation seems to deny a general right to secession of groups within a State”.

I believe that despite some ambiguity in international law, the various regions (states, cantons, provinces) of a Federation do not have a legal right to walk away from the union. A unilateral act of separation is permissible in confederations like the European Union or Asean but not in a Federation united by a written, supreme Constitution which describes the territories of the Federation.

Leaders of Sabah and Sarawak must, therefore, disassociate themselves from all separatist movements. Instead they must negotiate with the Federal Government about their discontents.

In turn, Federal leaders must recognise that Sabah and Sarawak’s restiveness is real and must be addressed. The Federal Government must return to the meticulously negotiated compromises of 1963. It must balance the concern of equity with efficiency in inter-governmental financial relations.

It must strengthen institutional mechanisms for regular, non-partisan dialogue between the centre and the states. If the root causes of dissent and disenchantment are addressed, this Federal union can survive the challenging decades ahead.

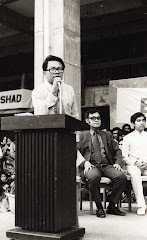

Shad Faruqi is Emeritus Professor of Law at UiTM. The views expressed are entirely the writer’s own.